Live Classes

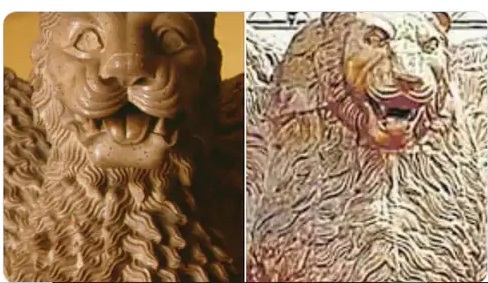

The lions lack the restrained modelling and elegance of the Ashokan original. They signify a muscular nationalism.

What is so disturbingly different about India’s national emblem as Indians know it and how the emblem has been conceived and represented at the new Parliament building?

For one, the ferocious expression on the faces of the new lions is qualitatively different from the benign aura of their back-to-back seated brethren on the Sarnath capital. There is absolutely nothing about their expressions which would remind us of the controlled modelling of the Ashokan specimens.

Rather, the new lions are more at home with a style that is widely seen in ancient West Asia. That style was excellently juxtaposed more than 50 years ago by S P Gupta in The Roots of Indian Art when he wrote that the Ashokan lions “were never expected to rouse fear in the minds of the onlookers while their West Asian cousins were invariably meant to inspire awe and fear”.

This is a prescient observation and makes me wonder whether the creators have imbued these lions with qualities that they associate with our modern rulers. Further, while the legs of the king of beasts at Sarnath are naturalistically depicted with a vein or two running in relief across some, the Parliament lions have prominent muscles and veins. The feel of brawny strength that this evokes is not seen in the more slender, restrained Ashokan form.

If those who conceived this version of the national emblem had paid some attention to history, they would have learnt a few things about how the Sarnath pillar capital and some of its features have been replicated and reimagined across time. In no instance in antiquity has any artist managed to capture the feel of the lions in their exquisite Ashokan form. The Gupta dynasty, for instance, is known for its beautiful art and architecture. However, when the lion-capital was copied at Sanchi by a Gupta sculptor, he could only manage “a feeble and clumsy imitation”. These are the words of John Marshall who was the director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India when the Sarnath pillar capital had been found. The modelling of the Sanchi lions of Gupta times, as he put it, exhibited “little regard for truth and little artistic feeling”.

The fabulously crafted second millennium CE dharmachakras of Thailand were more successful in the sculptural play of similarity and difference. The idea of a wheel of law on a pillar seems Indian-inspired but unlike anything Ashokan, the chakras often show inscriptions on the spokes and hubs. These relate to the Buddha’s first sermon at Sarnath and undoubtedly enhance the Buddhist aura around dharmachakras. The recognisable core of exemplary restraint that is central to the Buddha’s message and that of his most famous royal disciple, Ashoka, remains an integral part of the re-rendering. The modification is, thus, a kind of amplification of the original message.

Closer home, Jawaharlal Nehru too appropriated the Sarnath imagery and gave the ancient symbol a new meaning. He did not change its form but made the Sarnath pillar capital, which in Ashokan times was associated with the Buddhist faith, into the national emblem of a new country’s civilisational heritage. Some years later, Vasudeva Sharan Agrawala provided a historical anchor to Nehru’s idea by showing that this was “not a sectarian concept but was the fruit of a number of religious, philosophic and cult motifs which received approval for thousands of years in the accumulated tradition of the Indian people”. Both Nehru and Agrawala reshaped its meaning from its ancient Buddhist moorings to make it more inclusive.

This has now dramatically changed with the new lions. As a historian, I view the uproar about the ferocious roaring faces of this latest avatar of India’s national emblem as not being over various adaptations of an insignia, although the State Emblem of India Act does lay down that the state emblem “shall conform to the designs” as set out in the act. Instead, it is the fact that there has been a purposive transformation that has imparted a fierce aggression to the Ashokan lions that stands out. If some years ago, Ashoka was sought to be appropriated as a caste figure in Bihar politics, now his lions are being used to portray muscular nationalism.

The admirers of the novel parliamentary form can certainly claim that this is a new take on an earlier symbol. But the restraint in repose that is so unique to the lion imagery of the ancient Ashokan capital has become a casualty here. Because it has effaced that essence of the original, it is a conception that is entirely different from what we Indians see as our national emblem.

Paper - 1 (Ancient History)

Writer - Nayanjot Lahiri (professor of History at Ashoka University)

Download pdf to Read More